Japan and Methamphetamine: the Afterlife of Occupation and the Hiropon Age

Humanities

HIS 195A and HIS 195B

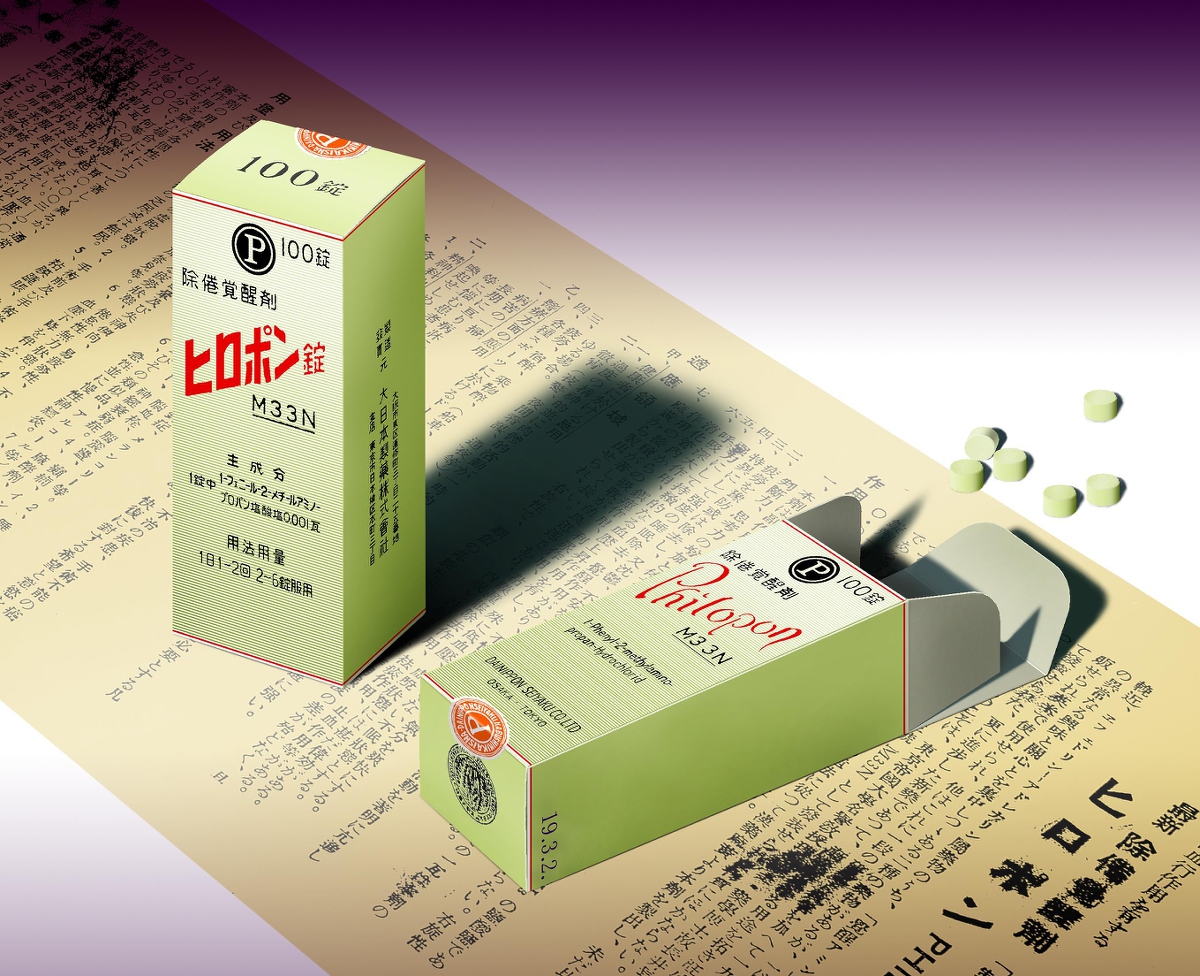

In this paper I argue that Occupation era narcotics control laws were not effective when first enacted and have distorted modern Japanese policy making. Following defeat in World War II, Japan experienced its first major drug epidemic in the Hiropon Age. Hiropon (a marketable moniker for the substance more commonly known as methamphetamine) was sold from 1941 as a productivity-enhancement drug in pharmacies to the Japanese domestic market. The Japanese military also utilized the drug to keep soldiers, pilots and industrial workers awake for longer periods of time and reduce appetite. Accordingly, in the postwar period, there already existed a large base of consistent hiropon consumers. After the infrastructural collapse of the Japanese state in the early postwar era, consumption trends only increased. During the Occupation era (1945-1952), the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (or SCAP) implemented sweeping ideological reform to Japanese narcotics control based on existing American policy. However, such reform failed to address the growing hiropon epidemic in favor of controlling substances like marijuana, heroin, opium and cocaine, which were more of a concern for American legislators than the Japanese general public as depressants were highly regulated in Japan during the pre-war and wartime periods. After the Occupation era ended, the Japanese state was left with few tools to combat the insidious public health crisis connected to "productivity-enhancing" hiropon. Despite this, the Hiropon Age only lasted from 1952-1956, likely due to high economic growth as well as effective grassroots efforts to combat hiropon addiction on a classroom and community basis. Today, Occupation era narcotics control laws are still in effect despite never having acted as an effective safeguard for public health.